Taking a bite of fresh bean pie in Brooklyn, New York City

Like many British children growing up in the halcyon decade of the 1990’s that gifted us with Pokémon, the Spice Girls, and David Beckham, Heinz Baked Beans was a staple dish on my dinner table every Fridays.

It wasn’t quite the Great Depression diet of George and Lenny in Of Mice and Men, nor the frugal World War Two economy crippled by food shortages, where Baked Beans were declared an ‘essential food item’ by the Ministry of Health.

At home, my mother had designated Friday dinners as cheese-and-onion-pasty with chips day, a carbohydrate feast of Tudor proportions accompanied with a hearty helping of beans. It was the perfect culinary marriage: the sweetness of the silky tomato sauce effortlessly seduced the tang of the cheddar cheese and soft onion of the pasty filling.

Even on school holiday visits to Bradford, my mother’s home-city, Baked Beans made a guest appearance at my grandparent’s bungalow, albeit with an undertone of Pakistani flavours. In her ingenious economy and efficiency as a mother raising nine daughters, my grandmother invented a Baked Bean curry with a base of caramelised onions fried with turmeric, green chillies, coriander powder, an egg added for good protein-measure, not forgetting a sprinling of freshly chopped coriander.

In a surge of misdirected nationalist pride, I confess thinking to myself once that Heinz was a British condiment. It turns out however that the man behind the bean(s) so to speak, was the American entrepreneur, Henry J. Heinz, who created his first product in Pittsburgh 150 years ago.

From what has metamorphosed into the staple of graduate student paupers and metropolitan city-dwellers in need of time-efficient recipes, Heinz first sold his newly patented tinned products in the UK at a branch of Fortnum and Mason’s in 1886.

However unique and inimitable his creation was to my juvenile taste-buds, Heinz’s invention was not America’s only dalliance with beans as I later learned on a visit to New York.

Abu’s Bean Pie Company in Brooklyn, New York.

In an inconspicuous looking bakery situated in Brooklyn, Abu’s Bean Pie Company is renowned for serving -you guessed it- bean pies.

Given my childhood nostalgia for beans, you can forgive this naïve Brit for imagining ‘bean pie’ as a glorious red lake of Heinz Baked Beans cradled in a crown of pastry.

Bursting with a custard-like filling of mashed navy beans, a dusting of cinnamon, milk, sugar, eggs, and surrounded by a whole-wheat crust, the bean pie is an American culinary institution, especially within the Black American community.

The pie was created by members of the Nation of Islam in the 1930’s, the black nationalist movement led by Elijah Muhammad that famously inspired Malcolm Little’s metamorphosis into the black radical, Malcolm X, though there are mixed accounts as to who exactly invented the bean pie.

In a tug-of-war between the Nation’s original founder, Wallace D Fard. Muhammad who apparently passed the recipe to Elijah Muhammad and his wife Clara, and boxing titan Muhammad Ali’s personal chef, the bean pie emerged from the Nation with a radical zeal amidst a burgeoning civil rights movement demanding racial equality and socio-political reform in the United States.

To create a cultural identity that distanced itself from the trenchant manacles of slavery, Elijah Muhammad promoted the pie as a replacement to the sweet potato pie.

As Zaheer Ali from the Brooklyn Historical Society relates, members of the Nation were encouraged to replace their surnames with ‘X’, a metaphor of their unknown African ancestors, many of them Muslim West African slaves who arrived during the antebellum period. It was a symbolic severance with the slave master’s name.

In the same vein, Elijah Muhammad encouraged Black American Muslims to also distance themselves from what he perceived as the “slave diet”. Sweet potato pie was a part of the soul-food canon inherited from slaves who left an ineffaceable finger-print on American cuisine and music, long before the nation’s inception.

In How to Eat to Live, a two-volume dietary guide for followers of the Nation, Elijah Muhammad lionised the navy bean as an elixir for prolonged life:

“…take little things such as beans. Allah (God) says that the little navy bean will make you live, just eat them. He said to me that even milk and bread would make us live. Just eat bread and milk—it is the best food. He said that a diet of navy beans would give us a life span of one hundred and forty years. Yet we cannot live ½ that length of time eating everything that the Christian table has set for us.”

Inexpensive and delicious, the pie quickly leapt onto the dinner tables and street-corners of America, and into popular culture through the hip-hop lyricism of Queen Latifah, Ice Cube and Common, even receiving a passing reference from Will Smith’s protagonist in the Fresh Prince of Bel Air.

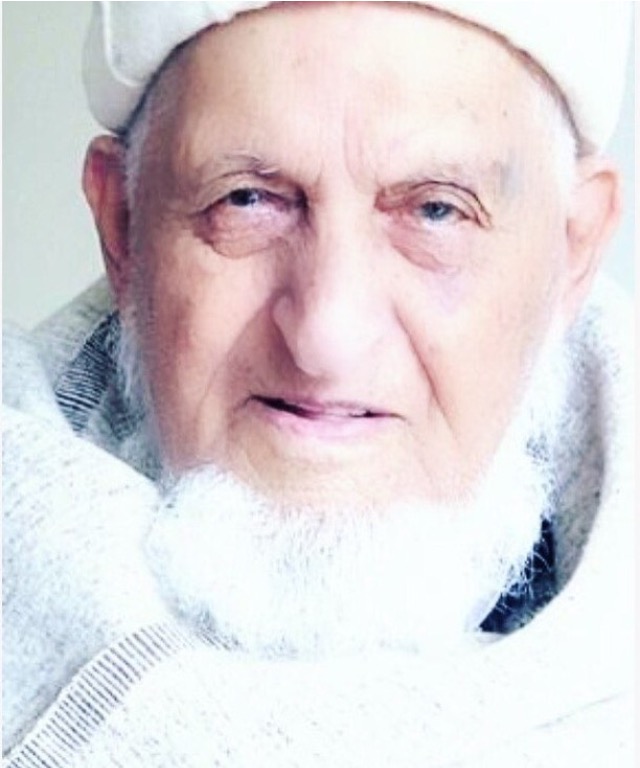

As I stood in front of the counter at Abu’s bakery, a newspaper cutting from the New York Times mounted on a frame to my right caught my eye. The face of Idris Conry, the founder of the bakery, smiled at me from behind the glass, reminding me of those Nation of Islam followers dressed in crisp two-piece suits and bow ties, standing outside mosques and road-sides, clutching at boxes of bean pies in one hand and copies of the Nation’s newspaper, The Final Call in the other, as they offered sweet slices of the Nation’s capitalism with an ebullient, “Bean pie, my brother?”

A member of the Nation of Islam carries a box of bean pies and a copy of The Final Hour (Credit: American Shaba’s Bean Pies)

Inspired by a cookbook that included a recipe for apple cake cherished by Muhammad Ali, Conry began baking as a teenager to the delight of those around him, selling cheese-cake and other baked goods using his home as a storefront, before opening Abu’s bakery in 2001.

An active member of the local community, Conry and fellow members of the mosque located a few doors down from his bakery single-handedly eradicated a crack epidemic that crippled the area in 1988 by patrolling the streets during a 40-day, 24-hour community patrol to ensure crack houses remained closed in the neighbourhood.

Now identified for being home to the only bakery in Brooklyn that produces authentic navy bean pies, my stomach fluttered with expectation as Rugi Jabie, a bright-eyed employee stood behind the counter behind an Aladdin’s cave of chicken patties, sweet potato pie, navy bean pie, and carrot cake, awaiting my order.

The cinnamon crust and custard layer of the bean pie are easily discernible.

She spoke with the relish of an oral historian, well-versed in the history of navy bean pie. “The navy bean is an American institution. It’s used in the navy, and even in our prison systems.”

Pointing to the white flesh in one of the pies that had been cut open which paled, quite literally, in comparison to the deliciously brown surface of one of the pies on the counter, she described the anatomy of the pie. “This top part is a crust made of cinnamon and other flavours that rise to the top above the custard that sets in the middle. It’s a custard-base pie, but it is filled with navy beans. Have you ever had a bean pie?” she interjected curiously. “No, I’m a bean pie virgin”, I said sheepishly. “Oh! I’ll tell you something, it’s changed people’s lives.” Something tells me she was not being hyperbolic.

Rugi Jabie stands behind the counter at Abu’s bakery, ready to serve bean pie

We continued to talk as my pie was warmed in the oven, discussing Alexandria Ocasio Cortez’s meteoric rise in American politics, and whether the mainstream feminist movement is intersectional in its inclusion of women of colour. It didn’t escape me that, as the pie’s radical origins dictate, my bean pie was inevitably served with an accompaniment of politics. On the house, of course.

“People eat these before working out”, Jabie said with glee as she handed a paper bag full of bean pies to a customer who has just ordered several large pies.

The said customer, Anthony, turned to me as though the phonetics of my British accent incriminated my penchant for Heinz Baked Beans, and chimed in, “The first time I had a bean pie was in the eighties. I was scared at first, because it was made of beans; I didn’t think it would be sweet. But once I tried it, I’ve been addicted to it ever since!”

He chuckled aloud when I asked if he had children and whether they enjoyed feasting on bean pie. “They love it. If I come through the door and I don’t have bean pie, I’m going to get in trouble,” he said before waving goodbye and departing with an armful of pie.

Anthony’s departure was a cue to attend to the bean pie that was sitting patiently in the palm of my hand, and so I perched myself on a stool near the shop-window with my bean pie and a steaming cup of coffee at the ready. I plunged my spoon into its depths, scraping deep into the bottom of the foil tin to ensure I salvaged some of the crust. Without hesitation, into my eager mouth it went.

It was as though a sumptuous cumulonimbus cloud of cinnamon and custard glided over my taste-buds. The biscuit-like texture of the excruciatingly thin crust offset the sweetness of the filling to perfection. This was no strange bean concoction, nor was it an attempt to dethrone Heinz Baked Beans. A heavenly cinnamon embrace enveloped me like a sweet furnace, warding off the biting sub-zero temperatures of New York.

Suddenly, the silence in the bakery was disrupted by the melodic sound of the Azaan, the Islamic call to prayer, crackling and floating along the bitterly cold Brooklyn streets from a speaker phone perched on top of the neighbouring mosque.

Allahu Akbar, Allahu Akbar, cried the faceless voice. God is great, God is great.

In that moment it seemed, the navy bean pie was even greater than God himself. Jabie smiled from behind the counter, knowingly like the prophetess of navy bean pie that she was, as my facial convulsions of sheer delight communicated what she had already predicted: With one bite of the navy bean pie, my life had change irrevocably. Whether my loyalties had switched from Heinz Baked Beans to the navy bean pie, only time will tell.

Sol, a waiter at 2nd Avenue Deli.

Sol, a waiter at 2nd Avenue Deli.